| Home | Books | Buy | Appearances | Op-eds | Reviews & Interviews | Bio | Contact & Media |

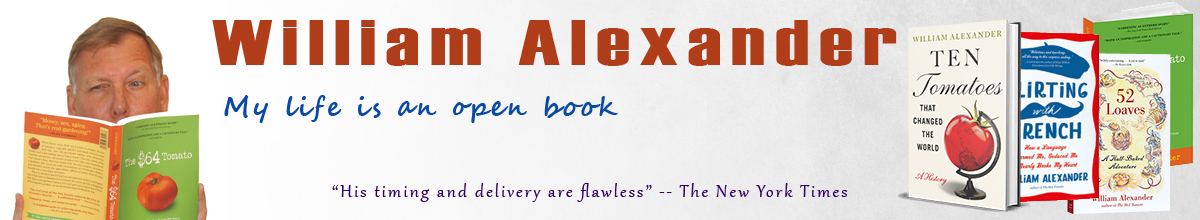

Ten Tomatoes That Changed the World

Reviews of

Flirting with French

The New York Times Book Review

Reviews of

52 Loaves

Chocolate & Zucchini

Reviews of

The $64 Tomato

| Boston Globe |  |

Alexander's breathless, witty memoir is a joy to read. It's equal parts fact and fun ... Alexander is wildly entertaining on the pageThere’s not much to a loaf of bread, right? Not so. For William Alexander, author of "52 Loaves," there are issues of the correct crust-to-crumb ratio, the right water content for the dough, the precise amount of rising time, kneading time, baking time, and temperature. You get it. On a mission not unlike Julie Powell’s quest in "Julie and Julia" to learn the recipes in Julia Child’s "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," Alexander spends 12 months baking a loaf of bread a week in search of perfection. He tasted it before years ago at a New York restaurant and is determined to reproduce the perfect peasant loaf himself. Alexander’s breathless, witty memoir is a joy to read. It’s equal parts fact and fun as he visits a yeast factory, enrolls in a bread-baking seminar in Paris, and wins second place in the New York State Fair bread competition, Category 02, Yeast Breads. He also peppers his narrative with insights into the historical significance of the staff of life. Like Powell, Alexander’s mission is about more than food. We get a hint of this when, en route to France, he tries to get sourdough starter (which looks suspiciously like plastic explosive) past an airport security checkpoint. He explains that an order of monks in France needs to learn how to make bread and that he has been asked to teach them. He is on "a mission from God."Alexander’s tongue-in-cheek embrace of the spirituality of his mission is reflected in his use of the monastery’s schedule of daily rituals as names for his chapters: Vigils, Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. The genesis of Alexander’s project springs organically from his life. A technology director by day, on nights and weekends he plays master gardener and baker to wife Anne and their children, Zach and Katie. He longs for a simpler way of life and favors the solace of the kitchen. “Bread baking is as homey, as removed from technology, factories, and engines, as you can get,’’ Alexander writes. He is a self-proclaimed “charter subscriber to the school of thought that ‘true’ bread, the stuff of peasants, has only four ingredients: flour, water, yeast, and salt.’’ Despite his distaste for social situations, Alexander is wildly entertaining on the page, dropping clever one-liners in the form of footnotes and parenthetical afterthoughts throughout. The irony of Alexander’s simple quest is apparent in its inherent paradox. Wheat cultivation is what allowed us as a civilization to quite literally put down roots. When we started growing crops, we no longer needed to move around in search of food. So towns started to develop, then cities, and factories. Alexander is intent on rejecting modern technology while making this simple bread, which is funny because it’s partly the bread we have to thank for modern technology. Still, his mission is admirable. While Alexander’s previous memoir, “The $64 Tomato,’’ chronicled the ongoing labor and arduous travails of backyard gardening, “52 Loaves’’ comes with time constraints. The one-year limit is both a source of stress and motivation as Alexander tinkers with his recipe. Frustrated that his bread is not producing the air pockets he would like, he goes through a “what does it all mean’’ phase, even turning to psychoanalysis for answers on why bread has become such a big deal to him. Borrowing a page from Robert M. Pirsig’s "Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance," Alexander concludes, "The perfect loaf was not something I was going to create; it was something that I was going to find. It was already there, waiting to be discovered or baked, but I had to elevate myself to reach it. It would not reveal itself until I was ready." As the adage goes, it’s the journey and not the destination. And for the reader, the trip is a gratifying one. |

|